From West to East and East to West: Two Views of America at the Carter

Now on view at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art (the Carter), two exhibitions offer differing (sometimes diametrically opposed) views of “America.” In Richard Avedon at the Carter, a celebration of the 40th anniversary of the famed photographer’s seminal project In the American West, a New York fashion photographer turns his camera to everyday people he met as he traveled through 17 western states. Paired with Richard Avedon at the Carter is East of the Pacific: Making Histories of Asian American Art, which explores the impact of the migration of people across the Pacific Ocean on American art, viewing American history through an immigrant perspective.

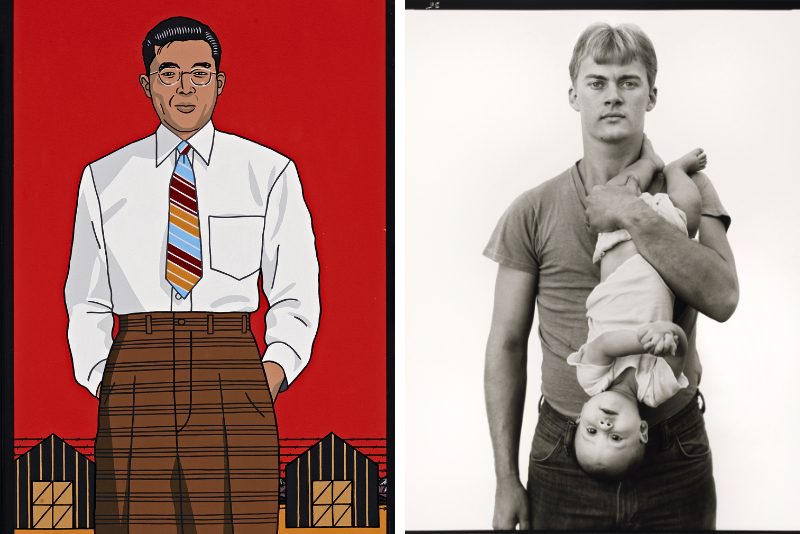

Left: Roger Shimomura (American, b. 1939), Business Man, 2008, acrylic on canvas, Cantor Arts Center, Stanford University. Gift of Marilynn and Carl Thoma, 2010.96, © Roger Shimomura

Right: Richard Avedon (1923-2004), John Harrison, lumber salesman, and his daughter Melissa, Lewisville, Texas, 11/22/81, gelatin silver print, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas. © The Richard Avedon Foundation

In 1979, Mitchell Wilder, director of the Carter, commissioned Richard Avedon to travel through the American West in order to capture his view of “the West.” At the time, Avedon was possibly the most famous fashion photographer in the world. His subjects included Marilyn Monroe, the Beatles, Andy Warhol, and Dwight D. Eisenhower. While he photographed Vietnam War protestors and produced a book with his classmate James Baldwin documenting the Civil Rights Movement, Avendon was primarily known for his works in Harper’s Bazaar, Vogue, and Life and his collaborations with Diana Vreeland, Christian Dior, and Calvin Klein.

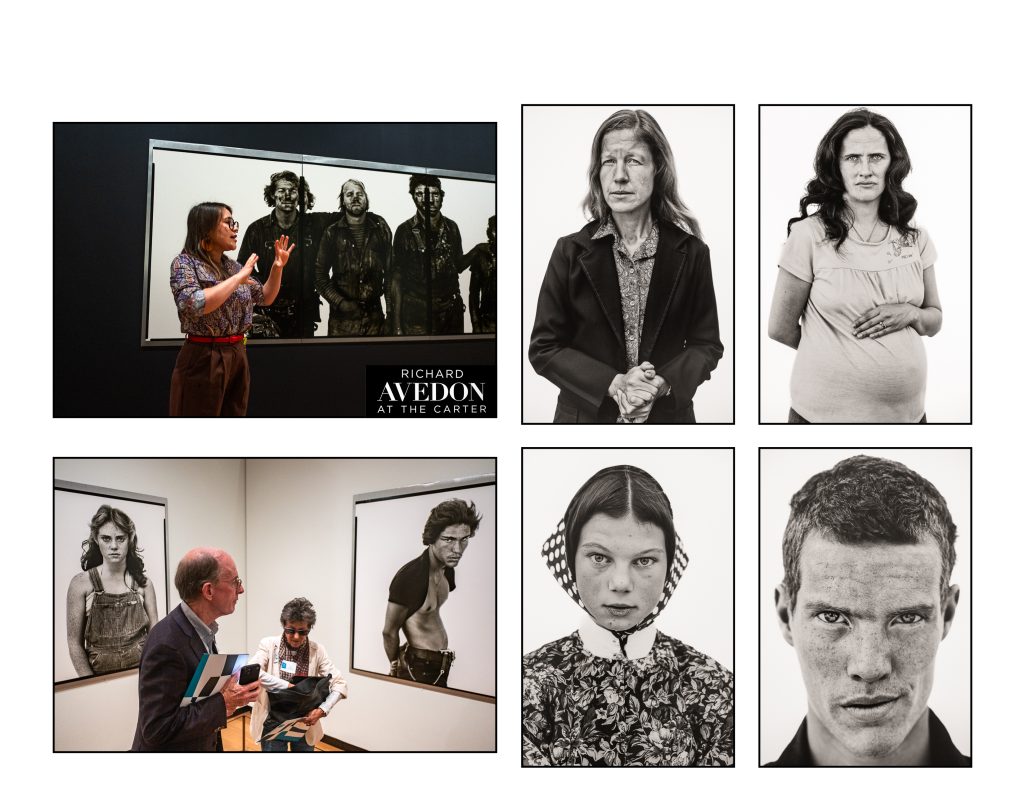

photo credit: Julio César Cedillo

From 1979 to 1984, Avedon traveled across the West. He and assistant Laura Wilson, a renowned photographer in her own right, conducted over 750 sitting, photographing everyday people against a plain, white backdrop.

The photographs that became In the American West as far from fashion photography as is possible. These weren’t glamorous shots of models and celebrities enjoying their good fortune. The photographs didn’t record the sentimental view of the West that was so prevalent with big, sweeping vistas and manly men doing honest work. These people were real. They weren’t glamorous. The photographs were stark and haunting. A drifter is juxtaposed with a couple dressed up in their Sunday finest. Carny workers and wildcatters and miners contrasted with a Huttite teenager and pregnant housewife.

photo credit: Julio César Cedillo

Reception to the collection was… mixed. Some reviewers applauded the honesty of the photographs, rejoicing in the way Avedon rejected the sentimental. Others railed against Avedon for taking advantage of his subjects. Still others were horrified by the fact that Avedon sought out the poverty and hardship that polite society chose to ignore or even actively conceal.

Regardless of the reviews, In the American West propelled the Carter from a small, regional museum to the internationally recognized institution that it is today, and Avedon viewed it as his best work. Richard Avedon at the Carter present 40 works from the series, as well as behind-the-scenes materials, including notes and memorabilia.

photo credit: Julio César Cedillo

Turning from the Eastern view of the West to the Western view of the East, East of the Pacific: Making Histories of Asian American Art asks, “What would it mean to understand the United States as being situated… east of the Pacific?”

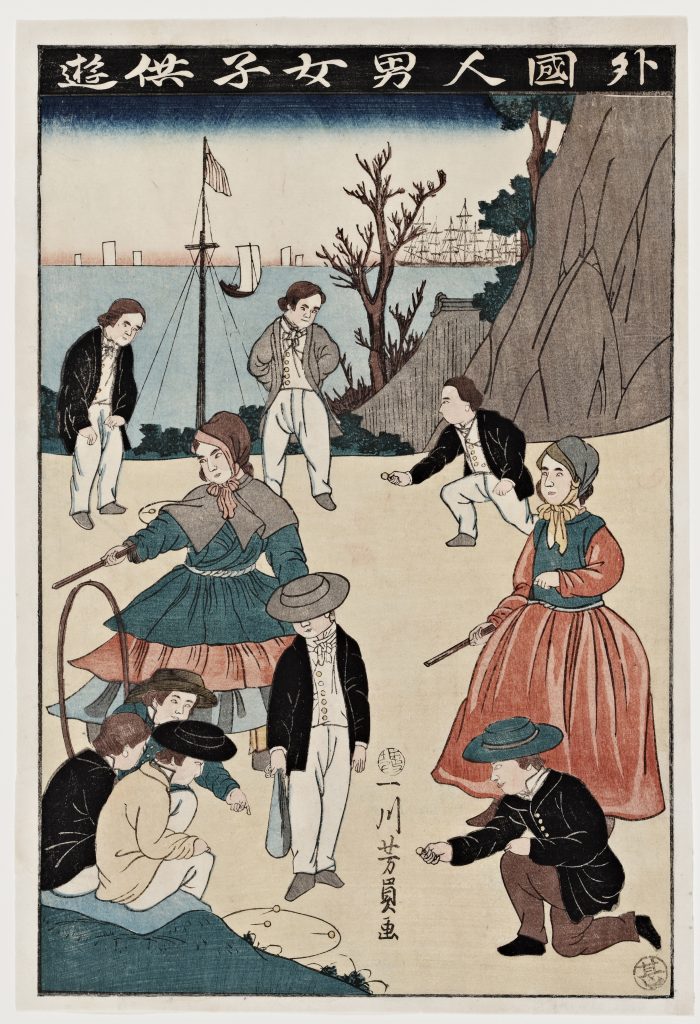

Utagawa Yoshikazu (Japanese, active ca. 1850–70), Foreign Girls and Boys at Play (Galkokujin danjo kodomo zo), 1860, color woodblock print, Cantor Arts Center, Stanford University. Robert E. & Mary B. P. Gross Fund, 2008.13

Forty-eight works from the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University ranging from the 1850s to the present tell the story of Asian Americans as they arrive in the United States and establish themselves as Americans.

By the 1830s, people from China, Japan, Korea, and the Philippines began to migrate to Hawaii, usually as contract workers on plantations. The first major wave of Asian immigration to the continental United States was precipitated by the California Gold Rush in the 1850s. These people built the Transcontinental Railroad and worked on California farms. Despite virulent and sometimes violent racism, they became an important part of the history of the West.

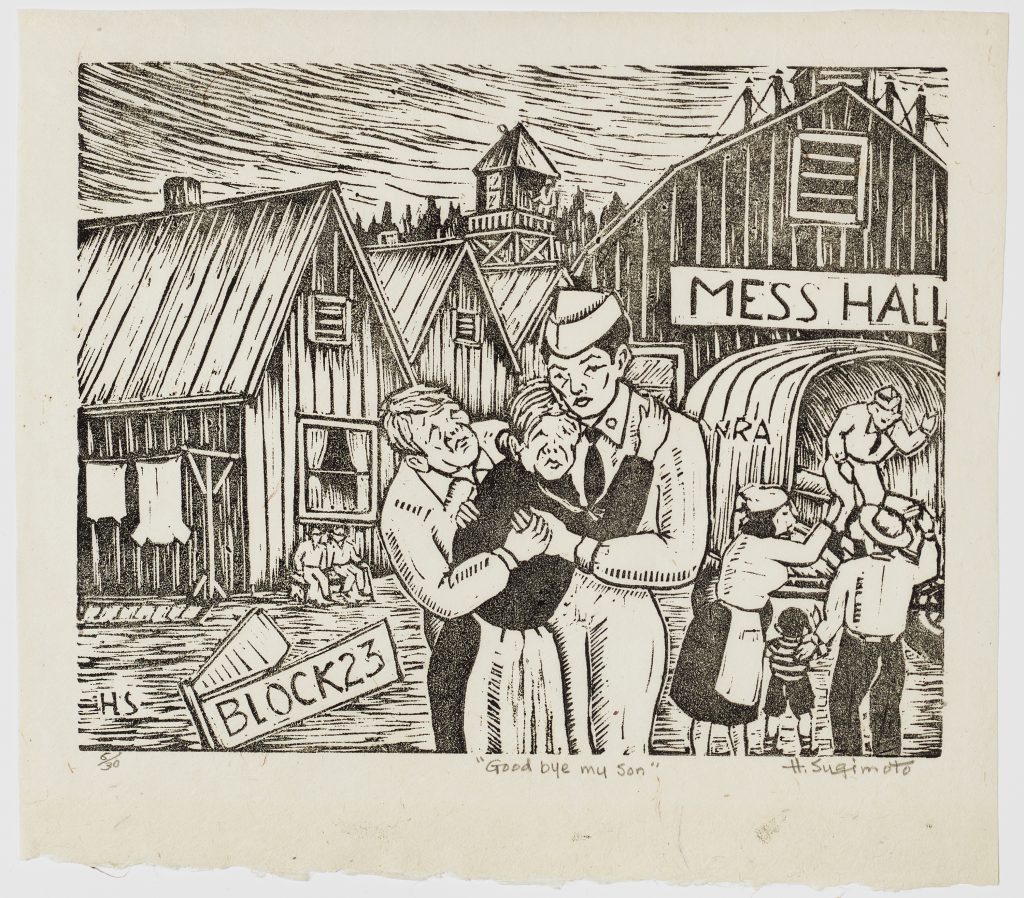

Henry Yuzuru Sugimoto (American, b. Japan, 1900–1990), Goodbye My Son, ca. 1965, linocut, Cantor Arts Center, Stanford University. Gift of Patrick and Sandra Hayashi in support of the Asian American Art Initiative, 2021.105, © Henry Yuzuru Sugimoto Estate

The works in the exhibition are presented chronologically, from works exploring the contact between the world the artists left behind and their new environment to abstract art by Asian American artists that contradict the current perspective that Asian Americans were not significant non-representational artists. There are pieces from artists working in San Francisco’s Chinatown and artists detained in concentration camps after Executive Order 9066 authorized the United States military and other federal agencies to forcibly remove Japanese Americans from their homes.

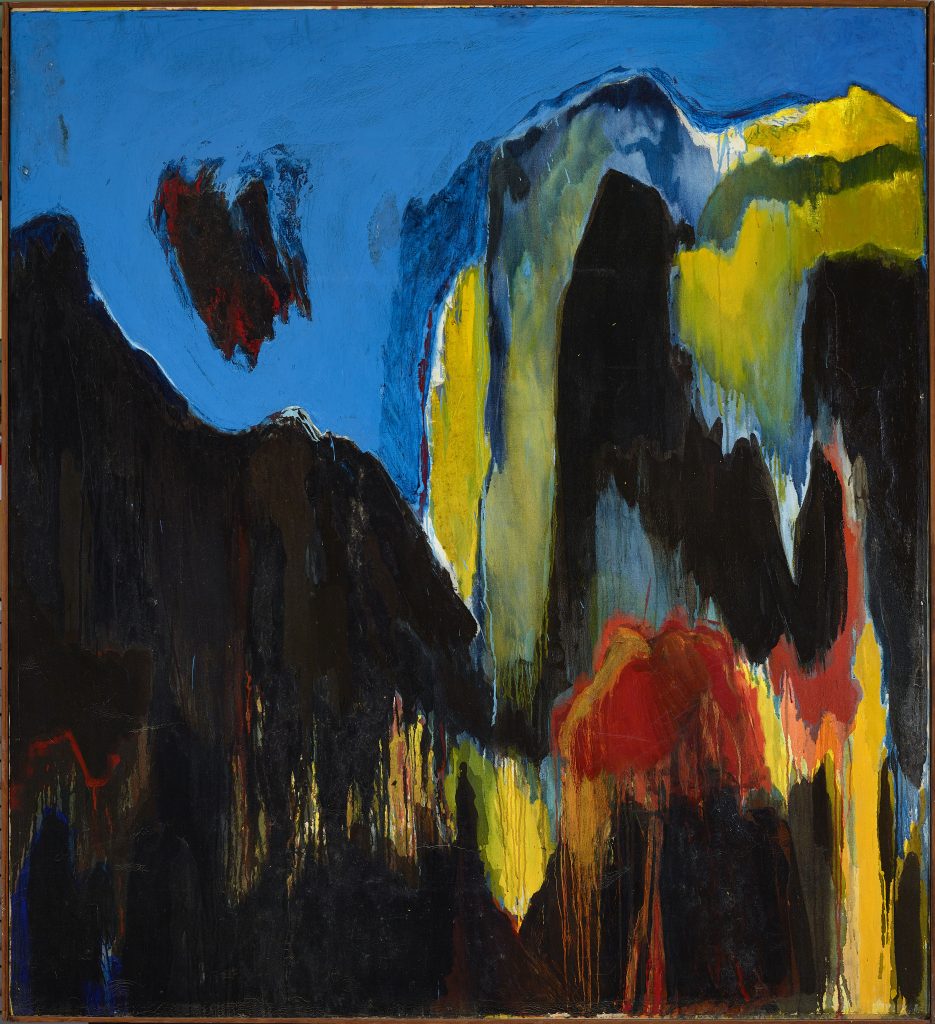

Bernice Bing (American, 1936–1998) Blue Mountain No. 4, 1966. Oil and acrylic on canvas. Gift of Alexa Young. Funding for the conservation of this artwork was generously provided through a grant from the Bank of America Art Conservation Project, 2020.14

By juxtaposing Richard Avedon’s photographs with the works East of the Pacific, the Carter has brought together two views of America. Richard Avedon was New Yorker who turned his camera westwards, while Asian artists documented their journey east across the Pacific.

Richard Avedon at the Carter runs through August 10, and East of the Pacific: Making Histories of Asian American Art runs through November 30.

Sign in

Sign in