Rethinking Rhetoric

“Am I using rhetoric right?”

Seeking confirmation for his understanding of rhetoric as duplicitous, empty speech, a relative asked me this question at a holiday party last year. He peered over his glass of merlot expecting an explanation, and I sighed audibly before saying, “How long do you have?”

As an assistant professor of English at Texas Woman’s University, people assume I have a menagerie of pet peeves about the use (and alleged abuse) of the English language. I am often asked to hypothesize as to why no one knows how to use a comma or to play therapist to those most concerned with texting’s effect on the writing skills of the youth. And yet, these self-proclaimed protectors of the English language never upset me more than they do with their flippant dismissal of rhetoric.

Pundits are quick to brand politicians as slick or silver-tongued for using rhetoric, and preachers warn congregations to be wary of the spellbinding effects rhetoric has on the mind and soul. In both cases, rhetoric is shunned for being dirty and divisive. In fact, most people adopt this definition of rhetoric with reckless abandon, but the hypocrisy is that such claims are stylistically sandbagged with a rhetoric all their own.

To put it another way, the increasingly popular negative connotation of rhetoric is hardly an accurate denotation of a concept that’s been around for more than a millennium. When we start to see rhetoric all around us, we can begin to shift our mindsets to appreciate rhetoric for how it empowers and connects us.

Making Sense of the World

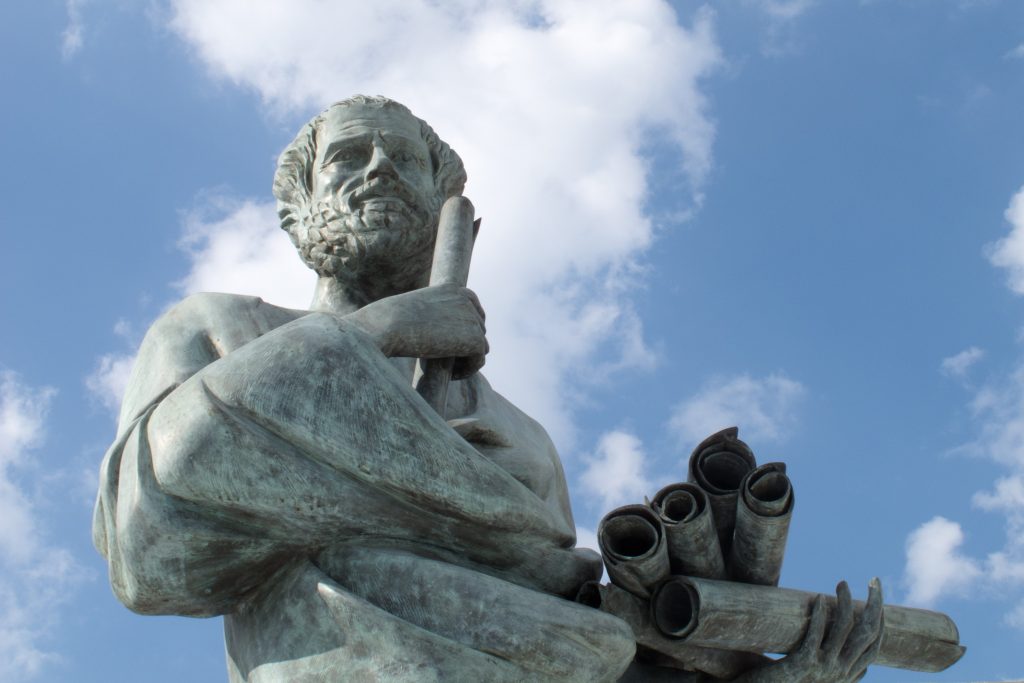

Countless and competing definitions of rhetoric swirl around in academic circles, but the most quoted comes from Aristotle: rhetoric is “the faculty of discovering in any particular case all of the available means of persuasion.” Aristotle also popularized the three means of persuasion taught in writing classes today: ethos, pathos, and logos. While the accurate translation of these ancient terms would take three more columns to unearth, briefly ethos is synonymous with ethics or credibility, pathos pertains to emotion and empathy, and logos is alliteratively associated with logic.

Another useful definition of rhetoric comes from communications professor Dr. Christine Seifert, who writes, “Rhetoric is how we use symbols, whether images or language, to make sense of the world around us and communicate our particular perspectives to each other.” When we start to think about communication in terms of simple symbols, we start to realize that a symbol is neither inherently good nor bad. It’s just a symbol – a grouping of words, lines, shapes, or even colors to which we ascribe meaning.

Seeing the Signs

Here’s a thought experiment I often give my students: Think about the traffic signs you encounter every day. Picture a stop sign. Ask yourself these questions:

- How does color make the sign persuasive?

- How does the octagonal shape make the sign persuasive?

- How does the font or typeface make the sign persuasive?

- What else about this sign persuades people to stop?

Now imagine all the stop signs in Fort Worth were pixie pink, shaped like ovals, and lettered in cursive script. You might wonder if you’re at a baby shower or the next stop on the Easter Bunny’s journey, not an intersection requiring drivers to stop, look both ways, and proceed with caution.

Consider the latent morality of the sign. The sign isn’t innately good, although it does keep us safe; nor is it bad, though it can be extremely annoying to encounter many stop signs when late for work.

Brushing aside baby dust and bunny humor, this thought experiment demonstrates the omnipresence of rhetoric in our daily lives. In the same way a fish can’t see the water it swims through, it can be difficult for people to notice the rhetoric that influences our every waking thought, our every uttered word.

Rhetoric is also more than mere words though. Rhetoric goes beyond writing and speaking into visual, tactile, spatial, or even gestural modes of communication. If this sounds abstract, remember the last time you saw someone wave two fingers to offer a peace sign. Or consider that every highway billboard is designed in a way that beckons you to try the “Best Coffee in Town” or to take the “Last Gas Stop for 50 Miles.” Commercials broadcast new shows you must watch, and social media platforms curate online storefronts you must visit. Everything is rhetorical.

Building Relationships

Here’s another quick thought experiment: Visualize the branding of a business – one you own or one you patronize. What colors, words, or icons does the business use to connect with customers? What’s the business’s purpose? What does the business offer its client base that makes it niche and necessary? And how is this business rhetorically composing itself in relation to other businesses?

Like rhetoric, businesses are everywhere. Most of us don’t stop and smell the roses, much less rhetorically analyze the businesses we use every day, but we are unconsciously processing the ways those businesses communicate with us. Increasingly, there are businesses that aim to have an impact on their communities by giving back. Rhetoric makes possible the success of a business as well as the relationships that businesses forge with communities. To quote famous rhetorician I.A. Richards, it would behoove us to remember that rhetoric “creates an informed appetition for the good.”

As tempting as it may be to find fault with rhetoric when things go wrong, we take for granted how often rhetoric makes things go right. Or as a former professor of mine, Dr. Abby Dubisar, would often say, “Rhetoric is how we get things done.” Every carefully crafted email sent, every firm handshake promising partnership, and every toddler meltdown averted is the reward of rhetoric used for the right purpose and at the right time.

So, the next time someone asks you if that’s a rhetorical question, say yes.

Sign in

Sign in