The Healing Fields: A Medical Mission Trip to Cambodia

On April 17th, 1975, Phnom Penh, the capital of Cambodia, fell to Khmer Rouge forces. Thus began one of the most horrific chapters in human history. The citizens of Phnom Penh were removed from their homes and forced out their city at gunpoint. Some 20,000 people were killed in the forced exodus. Those remaining were forced into the countryside to work as farmers, or into concentration camps.

Over the next four years, Pol Pot and his regime would go on to murder nearly 2 million people, over 25% of the entire population of Cambodia. Nearly all professionals and skilled laborers were executed or put into concentration camps with, invariably, the same result. In the name of Pol Pot’s agrarian utopia, teachers, lawyers, and doctors, along with mechanics and factory machinists, were targeted and killed. The result was a societal devolution unparalleled in modern history.

All manufacturing ceased to operate. All learning outside Khmer Rouge indoctrination efforts ground to a sudden halt. Any semblance of a justice system was replaced by the animal brutality of the Khmer Rouge. As doctors were either killed or fled the country, the medical needs of the population were entrusted to brutal youth medics, indoctrinated by the Khmer Rouge, who had little to no actual medical training.

Western medicine, thought by the Khmer Rouge to be a contrivance of Western capitalism, was banned. The medical library in Phnom Penh was burned. The entirety of medical knowledge in Cambodia was lost. Starting from scratch to understand the human body, the youth medics carried out horrific testing, examples of which are unfit for inclusion in this publication, on live, non-consenting “patients.”

Although it’s been forty years since the Khmer Rouge was removed from power, the country is still in the grips of a genocide hangover. The population, 50% of which is under the age of 25, lacks education and productive skills. Rural Cambodia, which by any standard can only be described as impoverished, lacks basic infrastructure. Cambodia is by every definition a poor, third-world country.

It’s not all bad news for Cambodia, though. Since 2000 the country has seen GDP growth of 7% to 8% per year, with textiles and tourism accounting for most of the increase. In fact, The World Bank recently upgraded Cambodia’s status from a low-income country to a low-middle-income country. While this will reduce Cambodia’s access to foreign assistance and will require the government to get creative in finding new sources of much needed aid, it is an indicator of a strengthening economy.

Photo courtesy of Michael Cowan

Phnom Penh, once ground zero for the worst genocide of the Cold War, is now a bustling metropolis of nearly two million people complete with modern skyscrapers and shopping malls sprouting up amongst its ancient Buddhist temples. Chinese developers are making significant investment in Cambodia, and for residents of Phnom Penh and other cities, this has resulted in increased quality of life and access to improved medical treatment and modern conveniences.

For rural Cambodians, however, not much has changed. While the threat of arrest, torture, and execution no longer hangs over their heads, the majority of Cambodians still live a life most accurately described as subsistence farming. They have little in the way of creature comforts and survive on what they can grow, hoping to sell what little is left over. A major challenge for most Cambodians is access to even the most basic medical care. Considering many Cambodians have never been seen by a doctor or dentist, the idea of consistent treatment options is unimaginable. While continuity of care is a distant goal, altruistic doctors, dentists, and nurses are doing what they can now.

Madeworthy sat down with Dr. Michael Cowan of Pediatric Urgent Care, who recently returned from a medical mission to Cambodia.

Photo courtesy of Michael Cowan

Madeworthy

Thanks for speaking with me today. How did this trip come together for you?

Dr. Cowan

My wife was out of town, and my daughter and I went to services at Christ Chapel one Sunday afternoon last fall. During the announcements, they said they were putting together a medical mission trip to Cambodia and if anyone was interested to come speak to them after the service. I don’t know why, but I immediately said to myself, “I’m going on that trip.” I had never been on a mission trip before, but I really felt called to go.

Madeworthy

So the mission was set up through Christ Chapel?

Dr. Cowan

Yes. Christ Chapel partnered with MANNA Worldwide, which is a non-profit with missions all around the world. They helped us develop our itinerary and with logistics and local resources like our drivers and translators. You can’t just turn up in a foreign country and say, “I’m a doctor and I’d like to treat people.” There’s a lot of groundwork to do beforehand, and MANNA Worldwide handled a lot of that for us.

Madeworthy

How many people were in your group?

Dr. Cowan

We had 25 total. We had three doctors, two dentists, and a physician’s assistant.

Madeworthy

What did the non-medical members of the group do?

Dr. Cowan

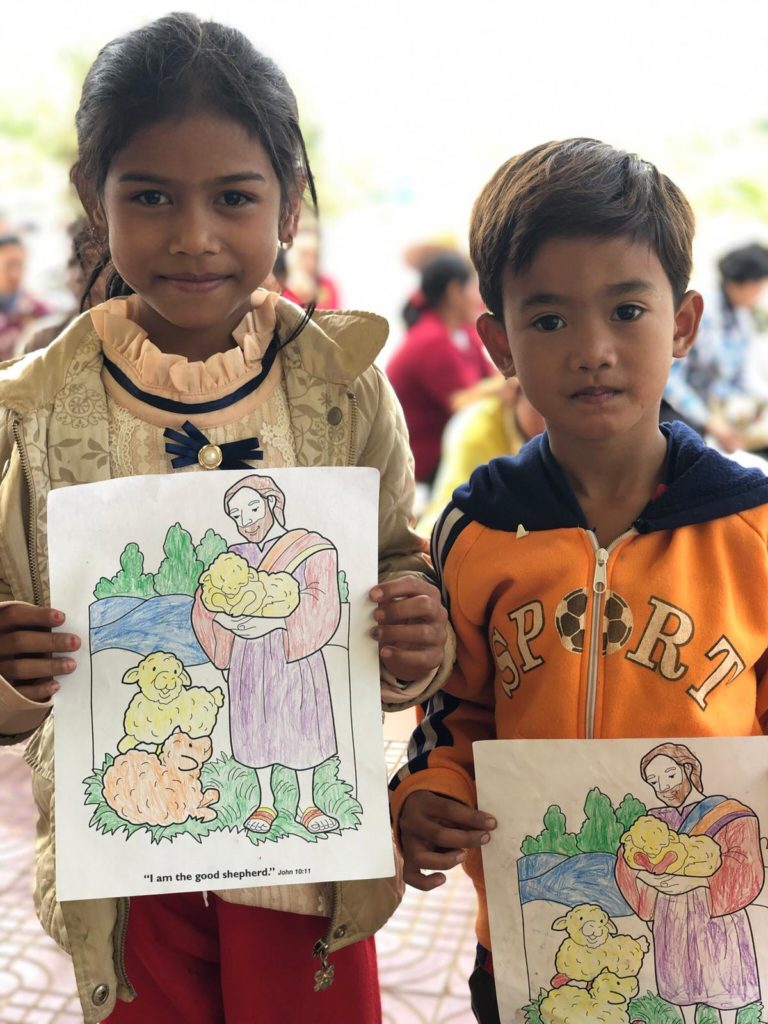

Well, it wasn’t a strictly medical mission. It was a religious mission, too. So most of the non-medical group members spent time with people spreading the word of the Gospel. On our first full day in Cambodia, we went to an orphanage run by Filipino Christians. They spent time with the children there. Cambodia is over 92% Buddhist, so they were spreading the message of Christianity. They also assisted us in our efforts. We had access to a lot of medications through a local surgeon, but we didn’t have a pharmacist. Some of the members of our mission acted as our pharmacists. I could diagnose someone with hypertension and write out a prescription on a piece of paper, and our folks would locate the meds, fill the prescription, and catalog all the medications. We also brought a lot of eyeglasses with us. We didn’t have an optometrist or ophthalmologist so members of the group would have people read an eye chart, and we could give them glasses based on those results. Many of them hadn’t seen clearly in years!

Photo courtesy of Michael Cowan

Madeworthy

What were your days like? Were you treating patients all day?

Dr. Cowan

Yes! Our first day when we were setting up to receive patients, there were hundreds of people waiting. We worked 12-hour days, and I can’t remember the last time I was that tired. I felt like I was a resident again. We would work all day, and when we got back, I would lay down for just a minute and then wake up around midnight. One day, we went to a Buddhist temple and set up our clinic right in the middle of the temple. The monks, I think there were about two dozen of them, all had scabies, and we treated them. Word had obviously gone around that we were there, because again there were a couple hundred people waiting to be seen. We treated people for all kinds of things. Scabies, lice, hypertension, GI issues. I am a pediatrician, but I was treating kids and adults. One man had a large growth on the side of his head that I removed under local anesthetic. He never moved a muscle. You would never do that here, but they don’t have modern facilities there. The dentists were treating people who had never had dental care in their lives. They were extracting teeth, and you could tell they were just making people’s lives better. It was amazing. One day we were setting up our clinic across the street from a middle school in this small town. I walked over to talk to the kids. They were all very friendly. The Cambodians love Americans! There was a white woman there. She was young, probably about 22. Her name is Mackenzie, and she is from Montana. She is spending two years there through the Peace Corps to teach the kids English. Later she came over to our clinic and spoke with us. She lives with a family in this small town in very primitive conditions. It’s just really impressive. I am very proud of her.

Madeworthy

You were mostly in rural areas, right? What were the conditions like?

Dr. Cowan

Yes. The people are extremely poor. They have nothing. They live in shacks, and they never complain about a thing. That’s one thing that really struck me. The people are all so kind and sweet, but if they don’t work, they don’t eat. Yet they never complain about a thing.

Photo courtesy of Michael Cowan

Madeworthy

Were there any cases or patients that you found particularly remarkable?

Dr. Cowan

Well, the man with the growth on his head for one. It was large and obstructive. He couldn’t sleep on his side, for instance. Having it removed was life changing for him. But the one that stood out the most was a little girl. She was five years old. She came to us to be treated for a skin infection. Many of these people had never seen a doctor before so I performed a full check up on them. Look in their eyes, ears, nose, throats. I listened to their hearts and lungs. This particular girl had a serious heart murmur. It was not slight. It was loud and very obvious. Probably no one had ever listened to her heart before. Through the local surgeon I mentioned before, we were able to arrange for her and her mother to go to the city so she could be seen by a pediatric cardiologist.

Madeworthy

What was your biggest takeaway from your trip? What did you get out of it or how did it change you?

Dr. Cowan

When I decided to go on the trip, I made a conscious decision to make sure that I was going for the right reason: in order to help others. To work hard and make other people’s lives better. Not simply to do something that would make me feel good, but to really put other people before myself. I think we all did that. We worked very hard. We treated over 900 people in the five days we set up our clinic.

Photo courtesy of Michael Cowan

Madeworthy

Do you think you would like to go back?

Dr. Cowan

Oh yes! I definitely want to go back. Because of what happened in the ‘70s, at one point there were only a couple of dozen doctors in the entire country. There is a medical school in Phnom Penh now, and doctors come from all over the world to give their time to teach and work with the doctors in the hospital. The young doctors there are all good, but they lack training. Many of their techniques are somewhat antiquated. I would love to go back and spend some time helping them learn some modern techniques. If I had the means, I would love to spend a couple of years and go to Vietnam and then Laos, where the conditions are perhaps even more primitive.

Photo courtesy of Michael Cowan

Traveling halfway around the world meets most people’s criteria for what an adventure should be, at least insofar as it is a physical undertaking. Traveling halfway around the world to give freely of your time and your talents in the name of helping others is beyond what most people consider an adventure. It goes beyond the mere physical. It is as much a spiritual undertaking as anything. Medical professionals like Dr. Cowan who sacrifice to work in Cambodia are treating more than individual patients. They are helping to heal the lingering wounds of a nation once torn apart.

This article is the cover story for Madeworthy’s Adventures Issue, May/June 2019.

Sign in

Sign in

Pingback: The Healing Fields: A Medical Mission Trip to Cambodia - Fort Worth Press