How Do You Paint a Breathing, Vibrant Person? Renoir at the Kimbell

Opened at the Kimbell Art Museum yesterday, the new exhibition Renoir: The Body, The Senses honors the master’s creative relationship with the female nude throughout his career and runs through January 26, 2020.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir

“Young Woman Braiding Her Hair”

1876

Oil on canvas

22 1/16 × 18 1/8 in. (56 × 46 cm)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Alisa Mellon Bruce Collection, 1970.17.63

Image courtesy of the Kimbell Art Museum

The Kimbell’s George T.M. Shackelford co-curated the show alongside The Clark Institute of Art’s Esther Bell. It represents the first show to focus on Pierre- Auguste Renoir’s portrayal of the human form in his work. Shackelford explains Renoir’s challenge, “How do you paint a living human body, a breathing, vibrant, real person, how do you paint them in light and the landscape?”

Guided by childhood visits to the nearby Louvre Museum, Renoir would become enchanted with masterpieces by painters like Courbet, Delacroix, and Peter Paul Rubens. He once declared of François Boucher, “No artist better understands how to render the body of a woman.” For this exhibition, the human form acts as a prism through which to view Renoir’s creative vision.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir

“The Concert”

1918–19

Oil on canvas

29 3/4 × 36 1/2 in. (75.6 × 92.7 cm)

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto. Gift of Reuben Wells Leonard Estate, 1954

Image courtesy of the Kimbell Art Museum

From realistic origins, Renoir’s bodies eventually grew to represent an experimental point of departure, allowing him to explore his passion for color, light, texture, and depth. Critics noted in response to his earliest nudes that the models needed washing because the skin tone was less ivory and more naturally flesh-colored.

From one gallery to the next, Renoir matures, his references to the masters of previous generations give way to a formal dialogue with contemporaries like Degas and his good friend Cezanne.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir

“The Bathing Spot, Study for the “Great Bathers”

c. 1886–87

Sanguine and white chalk on paper

28 3/8 × 37 13/16 in. (72 × 96 cm)

Thyssen-Bornemisza Collections

Image courtesy of the Kimbell Art Museum

A set of red chalk drawings indicate elements of the formative process for “The Great Bathers” from the late 1880s, where his naturalized sense of beauty transforms into a more abstract layering of shapes.

Crippled by arthritis in his later years, he would collaborate with sculptor Richard Guino on a series of sculptures. An example of the beautiful watercolors he based them on hangs nearby one of the smaller Venus pieces. His ability to verbally direct Guino’s manipulation of the clay is a testament to the depth of the artist’s drive and vision. It is profound to walk among these forms that he had imagined on canvas for more than 40 years.

All of these pieces reward in-depth viewing, which is especially true of his final masterpiece, “The Bathers,” where the exquisite brushwork melts in your eyes. In places, one can see where the paint was still dripping as he worked obsessively on the canvas.

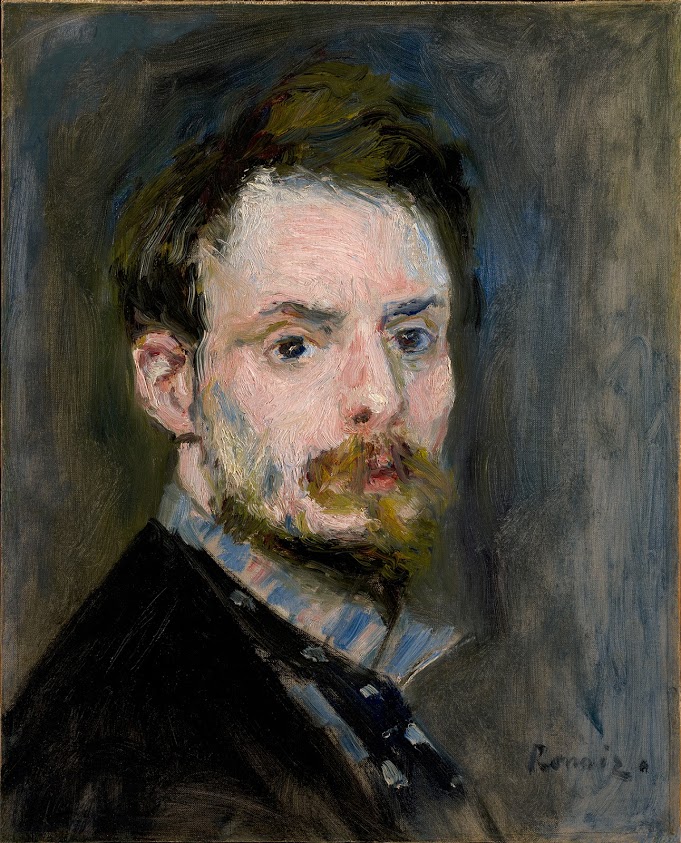

Pierre-Auguste Renoir

“Self-Portrait”

c. 1875

Oil on canvas

15 3/8 x 12 7/16 in. (39.1 x 31.6 cm)

The Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts. Acquired by Sterling and Francine Clark, 1939

Image courtesy of the Kimbell Art Museum

Renoir’s stylistic and intellectual impact follow in the final gallery, demonstrated boldly with Pablo Picasso’s magnificent Two Reclining Nudes from 1968, which powerfully ends the show by depicting the influence of Renoir’s work on the subsequent generation. Matisse remarked, “Time holds no nobler story, no more heroic, no more magnificent achievement than that of Renoir.”

An Austin native, Lyle Brooks relocated to Fort Worth in order to immerse himself in the burgeoning music scene and the city’s rich cultural history, which has allowed him to cover everything from Free Jazz to folk singers. He’s collaborated as a ghostwriter on projects focusing on Health Optimization, Roman Lawyers, and an assortment of intriguing subjects requiring his research.

An Austin native, Lyle Brooks relocated to Fort Worth in order to immerse himself in the burgeoning music scene and the city’s rich cultural history, which has allowed him to cover everything from Free Jazz to folk singers. He’s collaborated as a ghostwriter on projects focusing on Health Optimization, Roman Lawyers, and an assortment of intriguing subjects requiring his research.

Sign in

Sign in