From Vietnam to Ft. Worth: A Story of Perseverance & Faith

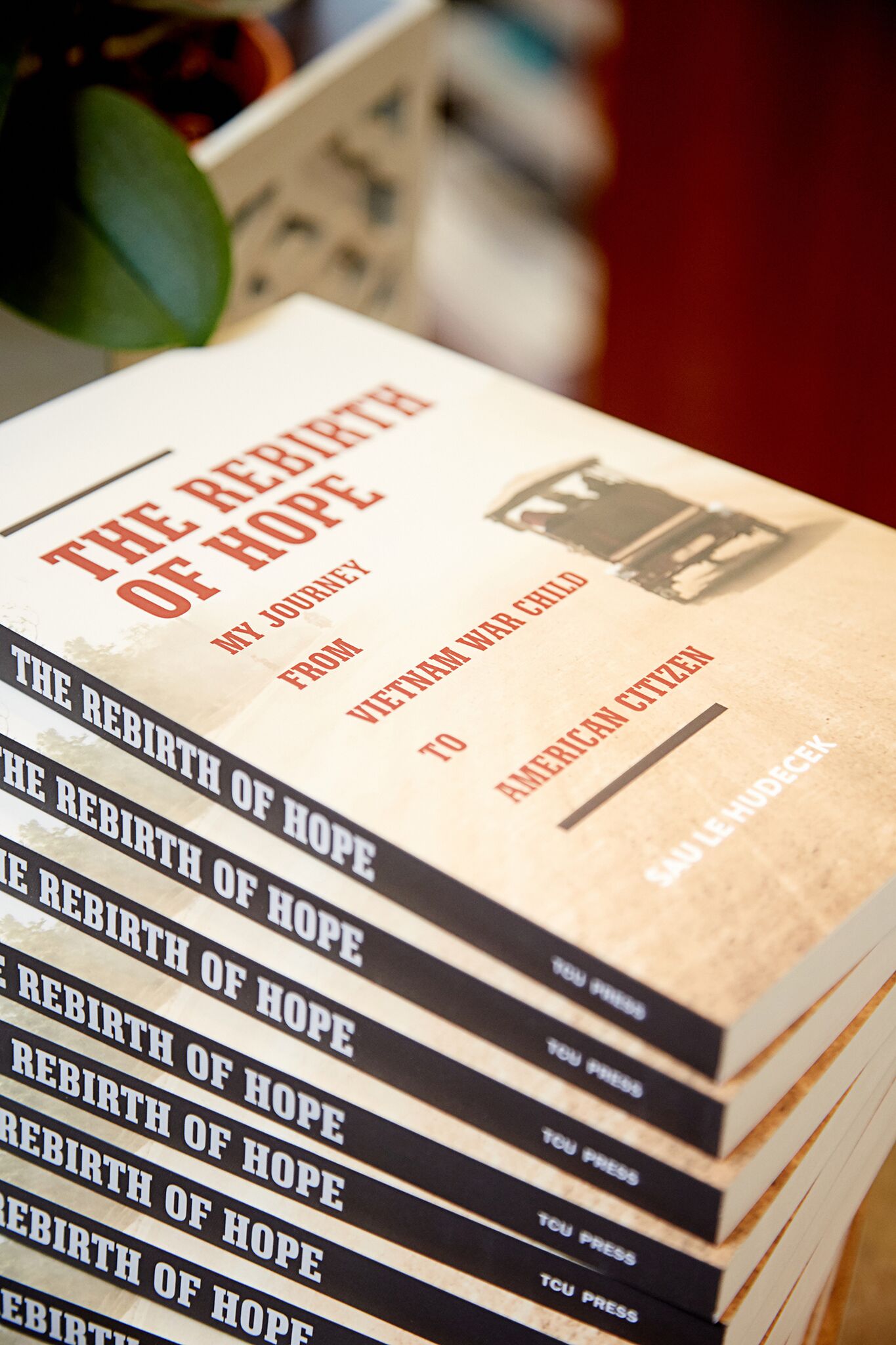

Set a bit incongruously, or perhaps anachronistically, on the corner lot of two residential streets in an established and affluent neighborhood north of I-30, the Jerrel James Salon caters to the cosmetological needs of many of Fort Worth’s well-heeled citizens. As I drive through quiet, well-lit streets on my way to meet Sau Le Hudecek, the owner of the salon, I pass pretty houses with manicured lawns and shiny new SUVs and sedans in the driveways. I am struck again by the shocking first sentence of Sau’s new book, The Rebirth of Hope, published by TCU Press:

“When I was six years old, the night before school started, my sister was killed by a land mine.”

photo credit: Kim Burnstad

As a child of the 1970s, the Vietnam war featured darkly and freshly in the sociological and cultural tapestry against which I and my fellow Gen-Xers were raised. Hollywood and New York churned out movies and books about Vietnam at a rate commensurate with the public’s appetite for them, which, in retrospect, seems to have been unquenchable. America was still wrapping its head around Vietnam.

More tangible to many of us, and often more tragic than any character in movies or books, were those men by and around whom we were raised that had been there, had seen it, and yet spoke not a word of it. As we were being born into a world of relative peace and harmony, our parents’ generation was physically diminished by an enemy chosen for them in a war entered for reasons not their own. Many of them bore or still bear the physical and emotional scars that are too often the legacy of war.

Later, as our young imaginations were filled with violent movie screen images of a beautiful place on the other side of the world torn asunder by a civil war that attracted foreign participants from around the globe, these silent, strong, yet often broken men kept their own counsel and so kept the lessons of war largely to themselves.

Something most of us never considered was the plight of children our own age who had, through no fault of their own, been born into a circumstance we could never comprehend. These kids’ lives were directed by the unpredictable vagaries of living in a war zone. When we went out to play with friends on the safe streets and sidewalks of Fort Worth, Texas, our biggest fear was crashing our bikes. Nobody I knew worried about stepping on a land mine.

photo credit: Kim Burnstad

Sau welcomes me into her energetic salon with a bright smile on her open, friendly face. She moves with the ease and grace of someone who is perfectly comfortable in her own skin, which, considering her childhood, is surprising. By Vietnamese standards, her childhood was deplorable. By American standards, it was unimaginable. Growing up in the 1970s and 1980s in post-war, communist Vietnam was difficult under the best conditions, but as the daughter of an American GI, it was downright dangerous.

Sau was the target of constant verbal attacks from “friends” and strangers alike, in addition to violent physical abuse, often at the hands of family members. Sau’s mother, a hard-working laborer who toiled daily just to keep her children alive, had little time to intervene in the constant abuse her youngest daughter received. She did, however, try to protect Sau in one desperate, yet humiliating way. She regularly took Sau to have the hair she had inherited from her African-American father which marked her as an outcast, shaved off. It didn’t help much. To Vietnamese eyes, Sau was obviously American.

It was a heartbreaking childhood made worse by the sudden, violent death of the only person who truly accepted her: her best friend and sister. That day, Sau’s life was changed forever by a long-forgotten, yet insidious remnant of a war already over.

photo credit: Kim Burnstad

INTERVIEWER You seem a very happy person, and you have an amazing capacity for forgiveness and for moving on. How is it that you can let go of the horrible things that have happened to you?

SAU LE HUDECEK You have to accept those that hurt you. Not doing so is a mistake, and you can’t penalize mistakes with mistakes. Love is stronger than hate. So, you accept them and move on. People blame others for their problems and point fingers, but you must take ownership of your problems. If you own it, you can change it. If you only blame someone else, that person owns it, and you cannot change it.

INTERVIEWER In your book, you describe a work ethic that is beyond most people’s idea of what is “normal.” After your sister died, you were left with two other siblings, a brother and sister. You worked very hard to help your mother, but they didn’t. Why do you think that is? Where did that drive come from?

SAU LE HUDECEK I wanted to be different. I saw how hard my mother worked every day to give us what little bit we had. My brother and sister only made demands on her. By the time I was four or five, I already had the drive to be different.

INTERVIEWER You worked in the fields with your mother. You had one set of clothing that had to last an entire year. You had to wash those clothes by hand each night with water you carried from a well. You attended school and did school work. You were beaten and bullied. How did you survive?

SAU LE HUDECEK In Vietnam, we did not speak of God. Ho Chi Minh was the god. What we learned in school was about Ho Chi Minh. God was not allowed. But I always knew there was a God looking out for me.

INTERVIEWER You were able to come to the United States because you are the daughter of an American serviceman. In your book, you say you have not sought out your father. Why is that?

SAU LE HUDECEK When I was a little girl, I wanted to have a father so bad. I wished for it every day. I didn’t understand why my father could not be there. Now, I know I don’t need a father.

INTERVIEWER Many of the stories you wrote about are very humorous. Upon arriving in America, you experienced quite the culture shock.

SAU LE HUDECEK Oh yes. The first day we were here, the wonderful people from Travis Avenue Baptist Church had filled our refrigerator, but we didn’t know how to eat it. We didn’t recognize anything as food. We tried to go to a supermarket, but we didn’t know how to buy anything. It was all so different. Now it is funny, but then we were just confused.

INTERVIEWER It didn’t paralyze you, though. You’ve been able to achieve such success here. Why do you suppose that is?

SAU LE HUDECEK You must be willing to ask questions and then listen to the advice people give you.

INTERVIEWER That takes a lot of humility.

SAU LE HUDECEK Yes. You must humble yourself, but people are often too prideful. You also have to trust others and take their advice. After I had bought some rent houses, my friend who helped me with the houses took me to Aledo to show me some land and told me I should buy it. I didn’t want to buy this flat, ugly piece of land. In Vietnam, if you have a field, you have cows, and I didn’t want cows. I didn’t really understand why he thought I should buy it. I didn’t know anything about mineral rights, or leasing, or the growth of the city. I didn’t ask him though. I didn’t listen, and now that land is worth so much! It was a mistake, but mistakes are lessons.

INTERVIEWER Ouch! That was a missed opportunity.

SAU LE HUDECEK Oh, yes. If someone gives me advice that I don’t understand, I know they are telling me this for a reason.

INTERVIEWER You have had some difficult times here in United States, too. Your first marriage, an arranged marriage, was to a man who didn’t take the transition to a new country as well as you did, and your marriage deteriorated.

SAU LE HUDECEK We did not see things the same way. In a marriage, you have to have the same goals, but that is not enough. You have to agree upon the path to achieve those goals. I worked hard and saved every penny. I bought a car that didn’t cost very much to repair. He bought an old wrecked piece of junk that was going to take a lot of money to fix. He also did not understand why I wanted to go to school at night to earn my cosmetology license. For him, my job cleaning hotel rooms was good enough. But it wasn’t good enough for me. I had goals that he didn’t believe in.

INTERVIEWER You dated some, but you wrote that it was never the right guy. Then when you met Don, you knew he was different.

SAU LE HUDECEK In Vietnamese culture, you take care of your parents, and they live with you until they die. American men didn’t understand that. And I had a son who I had to consider. Don accepted all of that. He accepted me for who I was and everything that came with it. Also, Scott [my son] immediately liked him which was important to me.

INTERVIEWER Before you and Don got married, there was another difficulty you faced that would affect you later. A rather large one. At one point, you had some medical issues and received emergency treatment that saved your life.

SAU LE HUDECEK I worked very hard, and one day I collapsed and was taken to the hospital. When I awoke, I was told that I had ovarian cysts, and the doctor had removed one of my ovaries. He also prescribed me birth-control pills to help keep my other ovary healthy.

INTERVIEWER That’s not what happened though.

SAU LE HUDECEK No. After I married, Don we tried to have a baby, but when I stopped taking birth-control pills, I had strange symptoms like hot flashes. We had some tests run, and I was told I was in early menopause. I couldn’t believe it. I was only 32 years old. But the doctor assured me I was never going to get pregnant because I was in menopause. After a sonogram, we discovered that the doctor who removed my ovary had actually removed both of them and prescribed birth-control pills to cover it up.

INTERVIEWER It’s shocking that something like that could happen. In the book, you mention that your doctor offered to testify on your behalf. Steering clear of any ongoing or potential legal proceedings, let’s discuss what happened next. As it turns out, you did get pregnant, and you have a daughter.

SAU LE HUDECEK My doctor suggested in vitro fertilization, and we decided to try it. We were a little bit worried about eggs splitting and having three or four babies, so we decided to have just one egg implanted. The doctors and nurses thought we were crazy because the chances of getting pregnant with just one egg were small. But I wanted it to be as natural as possible, so we left it in God’s hands and went with one egg. It worked, and now we have a daughter.

INTERVIEWER You’ve worked very hard, and, after a rough start and some ups and downs, life has turned out alright, hasn’t it?

SAU LE HUDECEK Yes, it has.

INTERVIEWER What do you think your life would be like if you hadn’t left Vietnam?

SAU LE HUDECEK I would not have met my husband or had my daughter. My son, Scott, would never have graduated from college. When I was a child, I remember looking up and seeing an airplane flying high above. I thought to myself, “I will never have a chance to fly in an airplane or drive a car.” Now I only see opportunity. Now I have hope.

photo credit: Kim Burnstad

As a child, being American made Sau a target for hate, but it was that same American heritage that gave her the opportunity to create a better life. It was an opportunity she has capitalized on. Arriving here in 1993 with $20, Sau knew nobody. She didn’t speak English. She didn’t have a job. In less than 25 years, Sau, now 46, has achieved so much. She owns a thriving business and multiple rental properties. She is also now an American citizen.

She is proud to be an American, and she is grateful for the opportunity America has given her. In fact, Sau’s new dream is to start a foundation to help the children of American service men and women achieve their educational goals. She says, “The men and women who served in Vietnam are heroes to me. All of those who serve, and their families, sacrifice so much for our country, and I want to do something to help them. “

The human capacity for suffering seems to be as individual as our fingerprints. Under extreme pressure, some break immediately, some bear it well only to break later, and some rise to the occasion and are called heroes. However, some simply take it in their stride. Viktor Frankl famously wrote, “Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances.” Although she has suffered much, long ago Sau chose humility, forgiveness, gratitude, and hope as the watchwords of her life. As a result, she is accomplished, successful, content, and fulfilled. She is a complete person, made whole by a life well-lived.

This article originally appeared in the January/February issue of Madeworthy magazine.

Sign in

Sign in